As promised, here's the second half of my guide to making 5e combat more engaging and interesting. This part is focused on ways you can speed up combat encounters to prevent them from bogging down gameplay. For the first part, on making combat more varied, dynamic, and interesting, refer to this post.

Speeding Up Combat

Providing interesting options is just one side of the coin. In order to make combat feel less like a slog, it helps to spend as little time in combat as possible. Sounds pretty reasonable, right? Especially when you have large numbers of enemies, rounds can drag on, and it can take longer than you'd like to even thin the enemy ranks to a reasonable level. But there are ways to deal with this too.

System Shock/Massive Damage

|

| Not everyone can keep on fighting this way. |

A few games, and a few editions of D&D, have a mechanic usually called System Shock, Massive Damage, or something to that degree. Sometimes it's a core rule, sometimes it's an optional rule. By default, 5e doesn't have one - but there are plenty of house rules people have shared out there. They all work a little differently, but the general idea is that an attack that does damage above a given threshold will have consequences besides merely losing HP.

What I do is that if a combatant is dealt damage greater than half of their max HP in one attack, they must make a CON save. If they fail, you roll on a table that can produce various consequences, which range from leaving them stunned for a turn to dropping them outright. This can make dealing a heavy blow even more satisfying, and makes for a more realistic effect where combatants can't necessarily keep taking heavy hits and stay fighting the whole time through. And of course, it gets enemies killed faster.

Minions

|

| These are minions. |

The most basic explanation of a minion is that it's a monster with one hit point. This doesn't necessarily mean the same thing as the monster being weak. It could still have attacks that deal a lot of damage, or it might have high AC. An ogre can be a minion, and its stat block would be completely unchanged in all respects but HP. They just die as soon as the PCs get a successful hit on them.

There are other traits to minions - to help counteract their low HP, they also don't take damage if they succeed on saves in the cases of effects where they'd ordinarily take half damage, and in 4e, they also dealt damage at fixed amounts rather than rolling. But it's up to you if you want to do these - the most important feature of minions is the single hit point.

|

| So are these. |

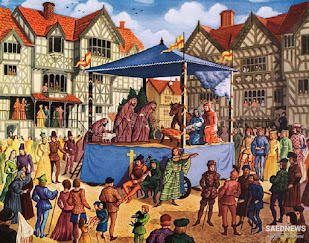

The idea behind minions is to simulate action sequences in movies in which the heroes mow down

hordes of enemies with ease. As such, they can lend a more cinematic feel to mass combat. They also cut down on the amount of bookkeeping you need to do to keep track of each enemy's HP, and can make battles against large numbers of enemies that would ordinarily take a long time go faster. If this is something you're after, it may be worth using. Some DMs prefer a more realistic, simulationist feel to their games, or they may feel like minions trivialize combat. I personally don't use minions, but they're certainly an option if you want to make combat flow faster.

Morale

|

| Sometimes, running away is the only Secret Technique you need. |

Among the OSR community, you'll find many people advising DMs to make morale checks for enemies. Imagine my surprise to find out that 5e does, in fact, support this! No one talks about it, because no one actually uses it. But it is in the core rules! As written, a morale check is a DC 10 WIS save. If the enemy passes, it stays in combat. If not, it immediately goes to disengage and move as far away from the fighting as possible on future actions. Yep, it's that simple!

I suppose that part of the reason people don't use morale much any more - in addition to just being accustomed to the more simplistic behavior of enemies in video games - is because the rules may be too simple. There's no criteria given for when enemies should start making morale checks, or what circumstances would prompt them. Some other bloggers have proposed more intricate systems, but I just go with my judgment on this. Essentially, I make a morale check for any enemies I believe would reasonably feel outmatched. For instance, if a group of enemies drops to half strength, those that remain might all make a morale check - if Morglub the orc just watched five of his fellow warriors fall to the party, why should he expect he'll fare any better, especially without reinforcements to back him up? Other times, I'll roll it if a single enemy was taken out in a particularly decisive or shocking fashion (you could even tie this into System Shock), wowing its comrades into thinking their foes are not to be trifled with. If the enemies don't have magic at their disposal and they just witnessed a magic-user in the party pull out a spell they can't hope to defend against, that could also tip them off that this is trouble. Remember, you're the DM - don't be afraid to make the call!

Unique Traits

|

| This... |

This isn't something mechanical to make combat faster, but I do think it's worth discussing here if I'm going to teach you how I run combat. In battles against groups of enemies, especially enemies that use the same statblock, it can get confusing who's attacking who, especially if you (like me) use "theater of the mind" combat without maps. Sometimes it can even be confusing for the DM if they don't know which enemy to deduct HP from after a successful attack! If we want to streamline combat to prevent it from becoming a slog, one easy trick to avoid this is to describe each individual enemy with an identifying trait.

For instance, instead of "the bandit Steve attacked on his last turn" or "the skeleton on the left", players and DMs can refer to "the bandit with the patchy beard" or "the skeleton in the rusted chainmail". These traits can be as simple as describing an enemy's hair color, or what equipment they're using, or distinctive marks like scars or tattoos, but if each enemy has one, it's much easier to tell them apart. Obviously, this works easier for humanoid enemies, not only because they can wear and wield different gear but because we, as humans, are better at noticing differences in things that look like us. If the party is fighting a pack of wolves, for instance, it might be harder to come up with a unique detail for each, but there's still plenty of options - maybe one has a scar over the snout, one has a notch in its right ear, and so on.

|

| ...not this. |

If you use miniatures, this may be a little easier, as players are able to visually identify the unique traits of different enemies and tell which is which on the tabletop if they can be seen in physical space. The downside of this is that you might need a lot of miniatures to make sure each is distinct enough to easily be referenced - though if necessary, the same model could be differentiated with different paint jobs.

An added bonus of this method is that, in addition to making combat move faster at the table, it helps add more detail to your descriptions and can better set the scene for your players. Describing each enemy differently makes them feel less like nameless, faceless video game mooks and more like individuals. Some enemies might become especially memorable through your embellishments in ways a generic description wouldn't accomplish!

Ending Combat Early

|

| It's probably best not to do this with your final boss, though. |

Finally, nothing speeds up combat quite like giving the players an option to bypass it or cut it short entirely. There are a number of ways to accomplish this - for instance, there could be some way to trigger a trap in the room that automatically takes out enemies, like dropping them into a pit (perhaps to make this happen, players would need to use alternate actions to operate machinery, as I discussed in our last installment). Or there might be a special item somewhere in a dungeon that could allow a fight to be avoided - perhaps an enemy is looking for something and will step down without a fight if it's offered, or a magic item could hold the key to instantly defeating a foe.

Some might find such battles anticlimactic, but there's a strong precedent behind this sort of thing. The Fighting Fantasy gamebooks often included tough fights that could be avoided if the player had a specific item or spell on hand, or else used an alternate route that got around them (if you aren't familiar with Fighting Fantasy, I can't give a big enough recommendation to Turn to 400, which will give you a good idea of what these books were like in addition to being one of the funniest blogs I've ever read). And many an old-school DM will advise against making every encounter rely on combat as the only solution.

It's important to keep in mind that both of these are relatively high-lethality systems, so a wise player would often use combat as a last resort. If the battle stood a high chance of killing the party, then most players would welcome a way around it! If you tend to run higher-powered games where PCs don't die as often, though, you may find players feeling this method is too easy.

Also, don't forget these don't have to be instant win conditions. Sometimes, the best course of action for PCs is to flee battle. When designing encounters, it's always a good idea to include something the party could use as an escape route, just so they know it's an option and don't feel forced into fighting a losing battle.

Do you have any other tips and tricks to make combat fun? Let me know in the comments!